Descending Through Arrays and Problem Solving

November 15, 2021

A Mystery is Afoot

Like many of the best stories in mathematics, our story today begins with playful pondering. We could be thinking of any number of things: a video game, a chore, opening presents for the upcoming Christmas, opening presents in a certain order, visiting indices of an array...

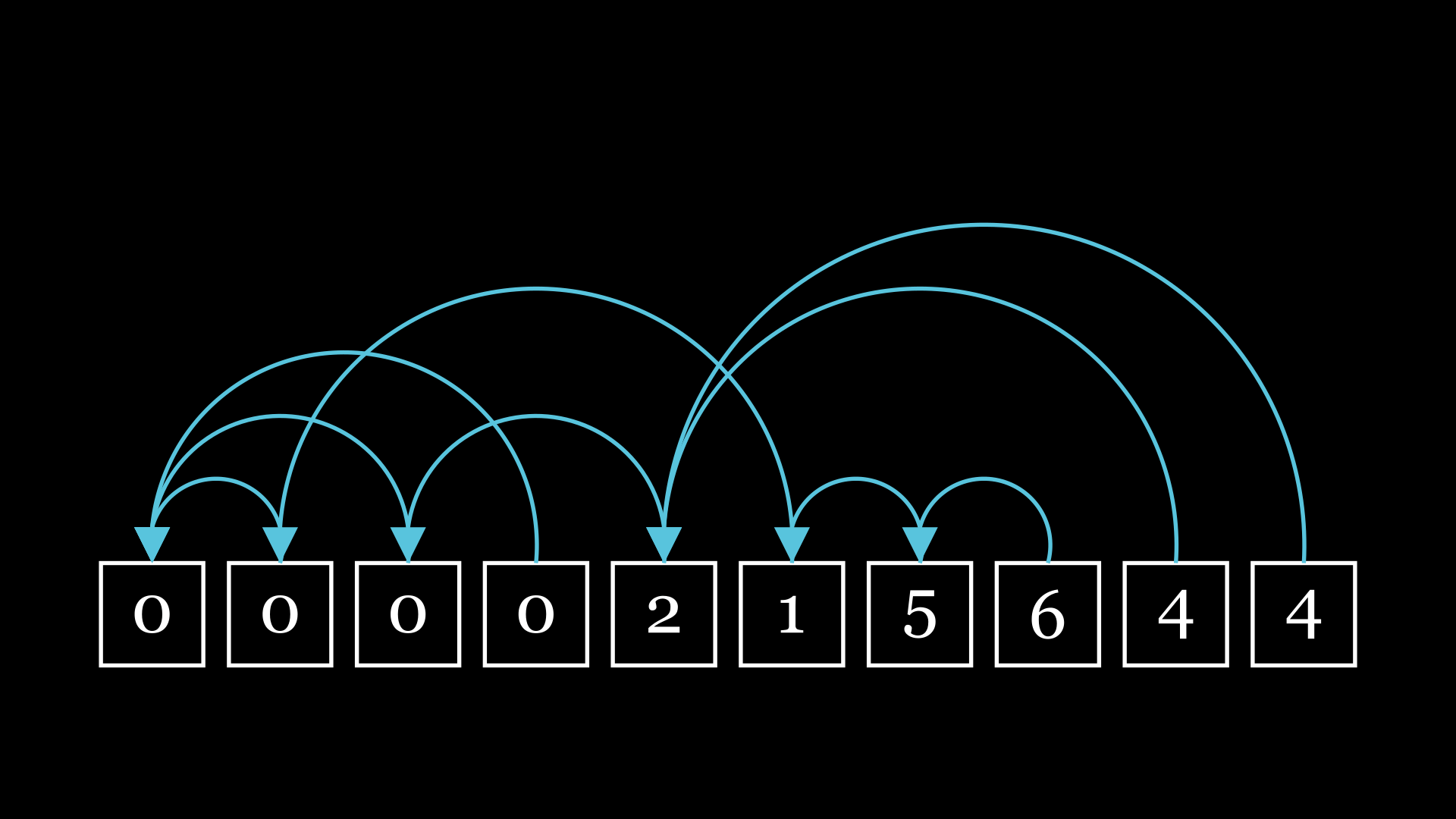

Well, there's an interesting thought. What if our Christmas presents contained a pointer to the next present in a sequence? Thinking more in the language of computer science, we might have an array containing

Now we're getting somewhere. If we start at the end of the chain and continually follow our references, we'll eventually wind up at our target.

But just one chain is boring: I want to know about multiple chains. What if I really want to get to the left quickly, but I end up having to go through every box? I wouldn't like that very much. It seems natural to ask, then, what the average behavior is. Specifically, I'm interested in the number of hops: if I repeat this process indefinitely, what is the average number of hops I'll go through?

More formally, we can say:

We're given an array of

values, each one (except the first one) randomly containing an index less than its own index. Starting at the last item and traversing the chain back, what's the expected amount of hops, , to get to index 0?

Well, this seems like an interesting math problem. It at least captured my attention when I first thought it up. Surely it's not novel, it seems like the type of thing that would be studied to death. But just seeing the answer is boring, I want to discover it for myself, and become a better problem-solver in the process.

Of course, I also encourage you to try the problem for yourself, before seeing my approach. You might also try pausing during the investigation if you spot where I'm headed.

The Crime Scene

I'm a programmer: when I see a problem where I can simulate the situation, my first instinct is to give it a shot. I began my investigation by writing some code to do exactly that in my language of choice, Python.

import random

# Let's try a few counts of items in our list

for n in range(3, 10):

# Populating our list with left-facing indices, except the leftmost.

ls = [0] + [random.randint(0, k-1) for k in range(1, n)]

hop_count, index = 0, len(ls) - 1

# Traversing down the chain

while ls[index] != index:

hop_count += 1

index = ls[index]

# Output our list and the hop count

print(ls, hop_count)Running this gives us some output that we can use to check for correctness:

[0, 0, 0] 1

[0, 0, 0, 1] 2

[0, 0, 1, 0, 0] 1

[0, 0, 0, 2, 0, 3] 3

[0, 0, 0, 1, 2, 3, 0] 1

[0, 0, 0, 2, 2, 0, 2, 0] 1

[0, 0, 0, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 1] 2

Confident that our simulation works, we might then try answering our original question empirically, using the highly rigorous method of "Run it thousands of times."

import random

import statistics

def trial(n):

# The above code, modified to only return the hop count for a single run

for i in range(3, 10):

# Get the mean of 100,000 trials for the current i

average = statistics.mean(trial(i) for j in range(100000))

# Apply reasonable rounding and output

print(i, round(average, 3), sep='\t')Running this gives us some numbers:

3 1.499

4 1.835

5 2.086

6 2.283

7 2.449

8 2.589

9 2.716

Now, that's a start, and is in-line with our trial run which mostly yielded low numbers. But, I don't see any clear pattern here. Some more careful pondering seems necessary. Our initial survey of the crime scene complete, we move on to more intensive forensic analysis.

A Familiar Fingerprint

As I pondered this, a familiar idea crept into my mind. I'd solved a few similar problems in the past, and that experience gave me an intuition. When looking at successive choices of random values, it can be helpful to choose the "middle" of the distribution. If we consider just one case where we're moving to a randomly selected spot to the left, on average, we'll land in the middle of that selection.

It seems reasonable that over one hop, we would cut the list in half, on average. Then after another hop, on average we would cut our initial list into a quarter. This type of halving comes up a lot in computer science: for example, in binary search or merge sort. When we see this type of halving, it's often indicative of logarithms being involved somehow. With binary search we have that our complexity from this halving is logarithmic,

From this, it seems reasonable to guess that our mystery function is

import math

# ...

for i in range(3, 10):

mean = statistics.mean(trial(i) for j in range(100000))

# A guess of log base 2

guess = math.log(i, 2)

print(i, round(mean, 3), round(guess, 3), round(mean - guess, 3), sep='\t')This gives us an output of:

3 1.498 1.585 -0.087

4 1.832 2.0 -0.168

5 2.086 2.322 -0.236

6 2.279 2.585 -0.306

7 2.453 2.807 -0.354

8 2.591 3.0 -0.409

9 2.721 3.17 -0.449

Well, that's unfortunate. The results tell us that our guess consistently overestimates the average, and also that it gets worse as

Since guessing the solution didn't work, we need to perform a more careful analysis.

A New Suspect

Since simply taking the midpoint of what remains in the list didn't work, we need to concretely look at what we mean by "average." Well, we know the usual formula for an average in school: if we have a list of items

But how do we apply this calculation to more wild situations, like our array chains? Well, we're uniformly selecting one of the next indices, and each of those indices surely has its own average. Couldn't we just take the average of averages?

By doing this, we can set up a recurrence relation. We have a base case that we know with a list of 1 index: since we're already at the start in that case, we have 0 hops. Then every index after that should just be one hop, plus the average of everything that comes after it:

This type of mathematical notation can be pretty confusing without some experience, so let's also get this translated into code:

# ...

# Our new guess for the count, based on averaging

def h(n):

if n == 1:

return 0

else:

# Computing the sum of every h(i) below the current one

sum_of_left = sum(h(i) for i in range(1, n))

# Computing our average, and adding one hop

return 1 + sum_of_left / (n - 1)

for i in range(3, 10):

mean = statistics.mean(trial(i) for j in range(100000))

# Our new guess

guess = h(i)

print(i, round(mean, 3), round(guess, 3), round(mean - guess, 3), sep='\t')After mulling over this result and running it, we see:

3 1.501 1.5 0.001

4 1.832 1.833 -0.001

5 2.081 2.083 -0.002

6 2.288 2.283 0.004

7 2.447 2.45 -0.003

8 2.594 2.593 0.001

9 2.719 2.718 0.002

Progress! Our function seems to closely match the prediction, much better than our initial guess. We might be tempted to call it quits here, but there are still questions to ask. For instance, does this function have a more elegant representation? Let's continue to investigate.

It took me quite a while to spot, but after turning the problem in our heads a bunch, we might happen to notice that the result of our function will always be a fraction. We compute it using only sums and divisions. It seems like it could be productive to see what those exact fractions are, so let's give it a shot. Modifying our code a little lets us do this:

from fractions import Fraction

def h(n):

if n == 1:

# Fractions will propagate up the call stack with arithmetic operations

return Fraction(0)

else:

sum_of_left = sum(h(i) for i in range(1, n))

return 1 + sum_of_left / (n - 1)

for i in range(3, 10):

guess = h(i)

print(guess)Which yields:

3/2

11/6

25/12

137/60

49/20

363/140

761/280

Now, the mathematically inclined might recognize this sequence on the spot, but I sure didn't. So I turned to the resource I always turn to when I see a curious sequence, the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, copied the numerators, and...

Eureka!

With just a few terms, the OEIS guessed the rest of the sequence. It looks like our values are the harmonic numbers

We might double-check our correctness by implementing it in code:

def harmonic(n):

return sum(1/i for i in range(1, n+1))

for i in range(3, 10):

print(h(i) - harmonic(i - 1))And running this verifies that they do indeed return the same output. This gives us a prime suspect, but how can we be sure?

Making our Case

There are a few ways that we might go about proving that our recurrence relation and the harmonic numbers are equivalent. When I first approached the task, I went on an algebraic crusade that involved a lot of difficult leaps in logic, eventually winding up at the conclusion that they were equivalent.

But math at its best, much like software engineering, is collaborative. So I turned to some friends to ask if they could find a better approach.

Sure enough, one of them did. Compared to my hard algebra, they found a very pretty way to reorder and substitute the two functions, which lets us reach a known property of the harmonic numbers, that

Now we consider the equation for

Since we suppose that

And since

Pulling down our earlier equality:

Which is true by the definition of the harmonic numbers. Q.E.D.

Into the Rabbit Hole

We've solved our initial mystery: we set out to find the average behavior, and after a false start and a few struggles, we eventually found our suspect and proved they were the murderer. But if you recall, at the beginning of our case we saw the fingerprint of someone familiar, a fingerprint indicating something deeper is at play. Why was our initial guess wrong, what distinguishes this situation from other halving algorithms? Why did the harmonic numbers show up? Can we refine our intuition?

In my opinion, these are the types of questions that allow a problem solver to transition from good to great. To not only answer a question, but to really solidify our understanding of that answer. To challenge ourselves to thoroughly eviscerate the shroud of mystery.

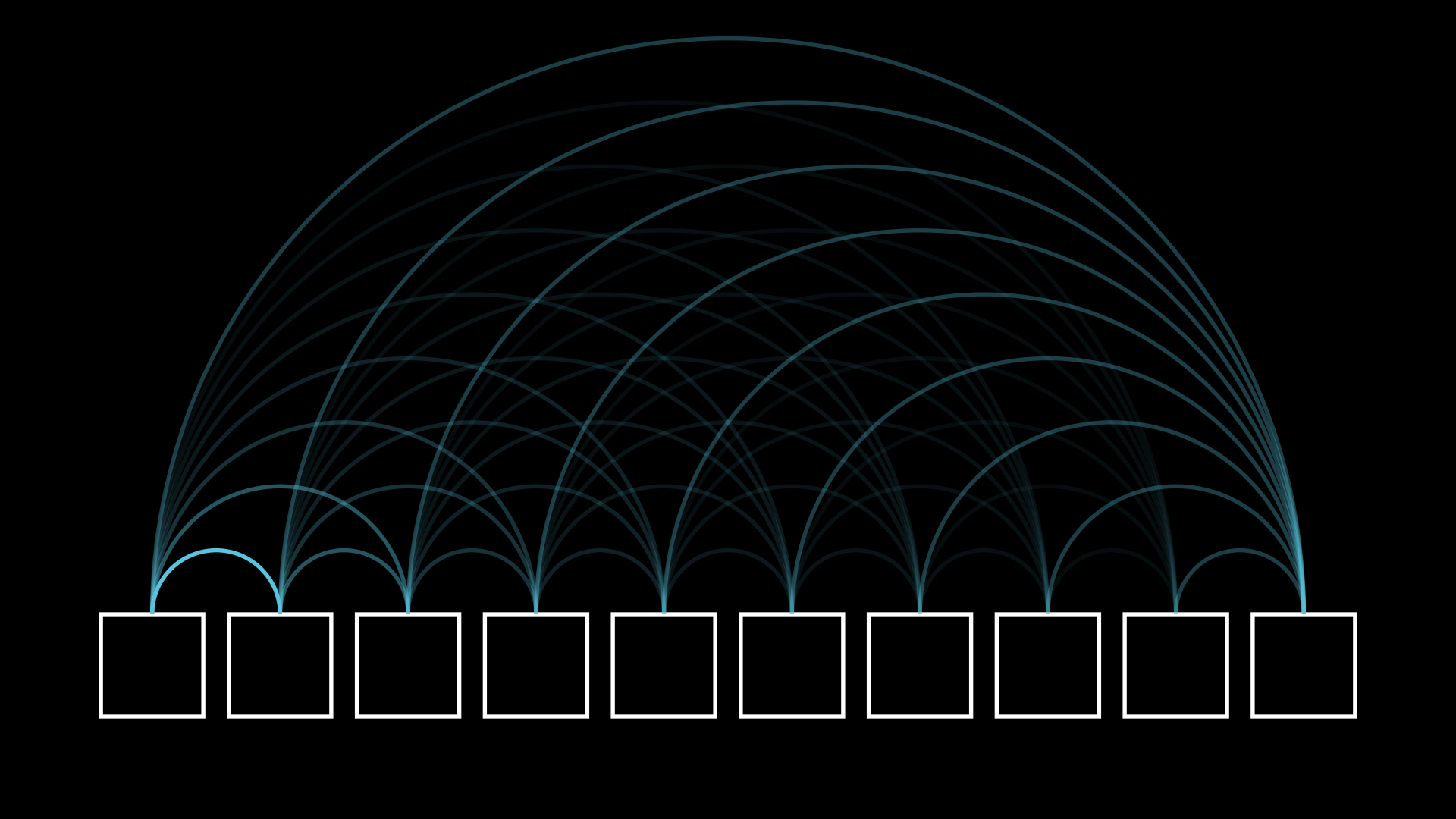

These questions all have their own rich answers that I think are best found through exploration. For example, in attempting to deduce why we found the harmonic numbers here, we might wonder about similar stochastic processes, leading us into the realm of absorbing Markov chains, where geometric series are plentiful. Or maybe for repairing our intuition, we might try to visualize every possible path, and see if we can pick up any insight from the resulting asymmetries.

So, with all that said, let's all try to have a little more fun with our problem solving and our explorations: challenges are the best teachers, fun challenges even more so.