Data Mining my Favorite Game

February 17, 2022

At this point it's probably no secret that I love Python. Slightly better-kept is the fact that I love this game called Go. It saw a bit of a surge in popularity in the west after DeepMind's AlphaGo beat one of the top players of the time, myself being one of many to hop on the bandwagon of new players.

It's somewhat rare for the two hobbies of programming and Go to intertwine; however, you've seen the title, so you know that I'm going to be applying some data mining to this game. Yes, you're right. But before then, I need to set the stage for what data I intend to mine, and why it matters.

Introducing Go

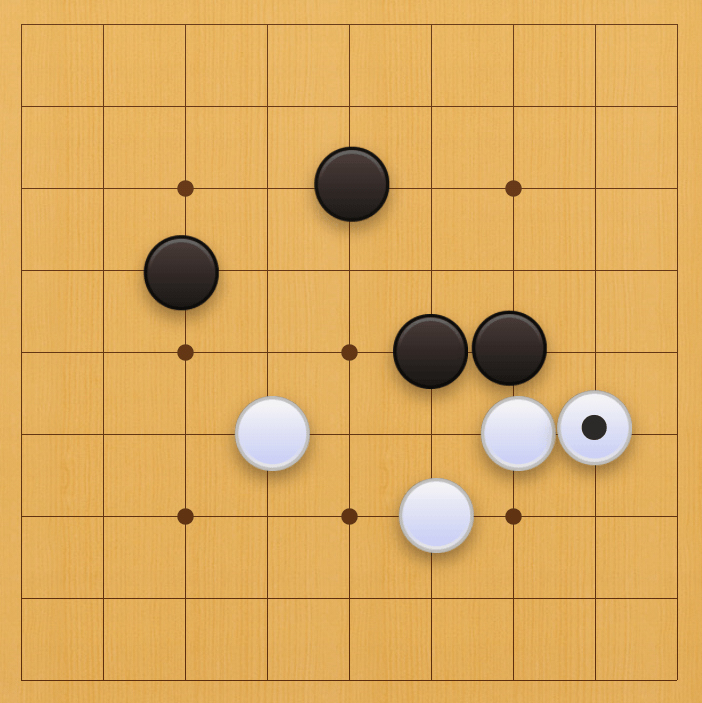

At its core, Go is a game about efficiency. I'm also a programmer and a math hobbyist, so it's not too hard to see why I might be pulled into it. The goal is to surround territory: you win if you surround more points than your opponent. Consider the start of this game:

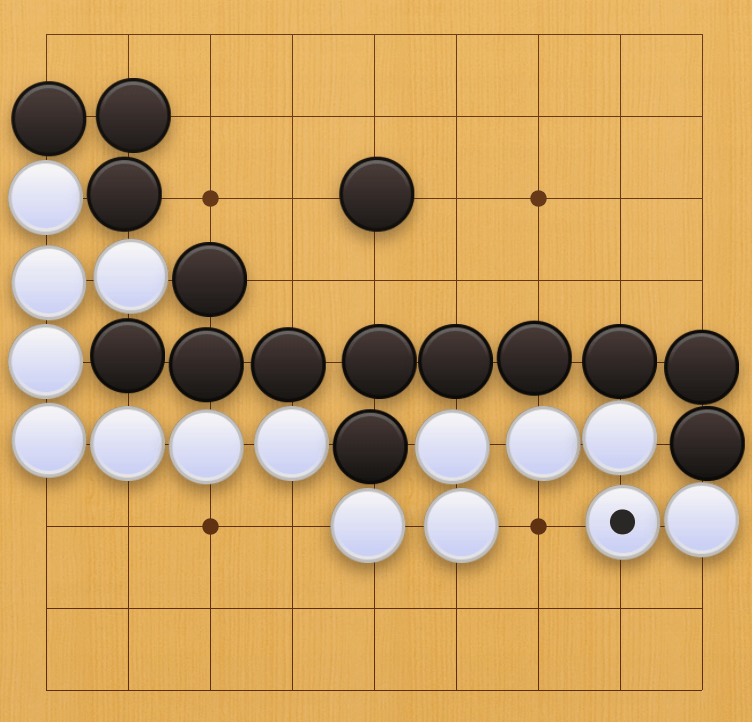

Both players have placed four stones on the board, and with those stones, they've started to claim some space. Black seems to largely be asking for the top of the board, while white is largely asking for the bottom. There's a lot of uncertainty in the position, but this is what we would expect. If we follow the simplest sequence of events, where both players get exactly what they ask for, we get something like this at the end:

In this game, White has surrounded 23 points of territory (

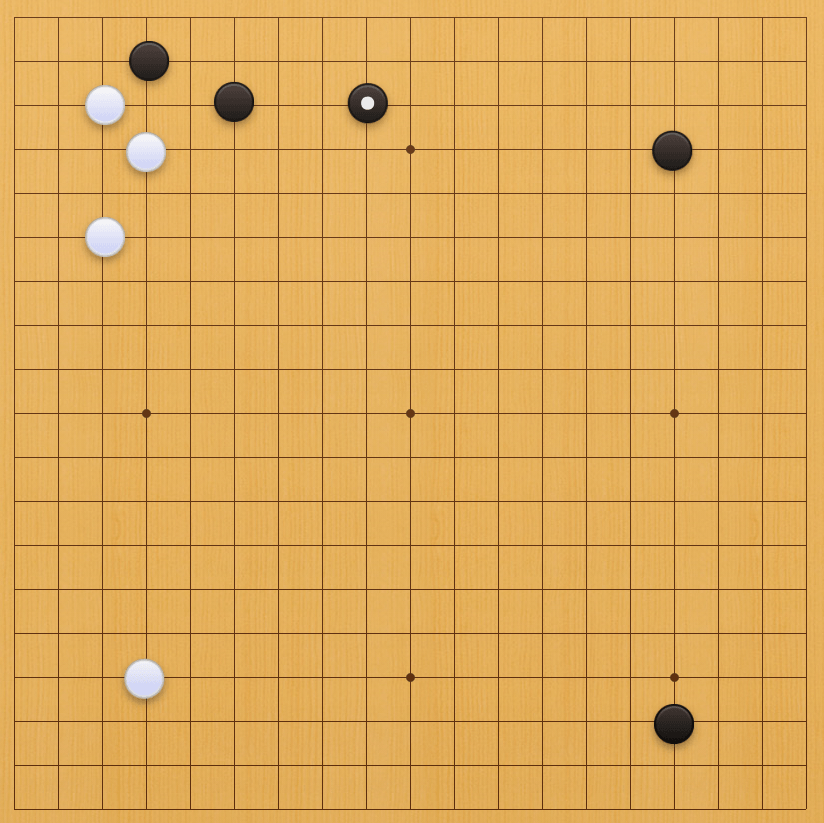

On a full-sized 19x19 board (as opposed to the 9x9 above), there's a lot of known sequences that are considered roughly equal for both sides. That is, when both players play in a certain way, there's an understanding that both are getting somewhat equal compensation for what they put in. For example, consider this board, particularly in the top left:

In this position, both players asked for two corners, and then Black took a slice out of White's top-left corner. They also both do it with only three stones, which is fairly efficient. The top-left is an example of one of these sequences: the corner is split roughly in half, and both players are satisfied with the result. These sequences are known as joseki, and while they're far from the most important aspect of the game, they demystify a lot of the early game.

These joseki are the primary focus of our project today. It's important to know at least a few of them when playing, and naturally, the first question a beginner might ask is, "which ones do I learn?" Now, there are a lot of resources on what joseki to learn and how to learn them. But a natural next question is, "which joseki do others play?" This is the main question I'm going to strive to answer, because knowing which joseki are most common can be a valuable teaching tool.

To Data-mine a Game

In order to get data on joseki played in games, we need games. There are many databases online for professional Go games, played by some of the strongest players the game has to offer. These are really valuable resources, but they're not of interest to me. First, because many people have done a version of this on pro games, and second, because I am not a pro. I want to know what is most often played by amateurs like myself, and that requires studying amateur games.

The database I'm using is from the Online Go Server, which has over 25 million games stored in about 80 gigabytes from 2013 to now. Something to note is that joseki will often go in and out of fashion, so I'm mostly interested in somewhat recent games, say from 2021 onwards. So the question has transformed from an abstract one of "which joseki do people play most often," to "how do I extract sequences from 80 gigabytes of games?"

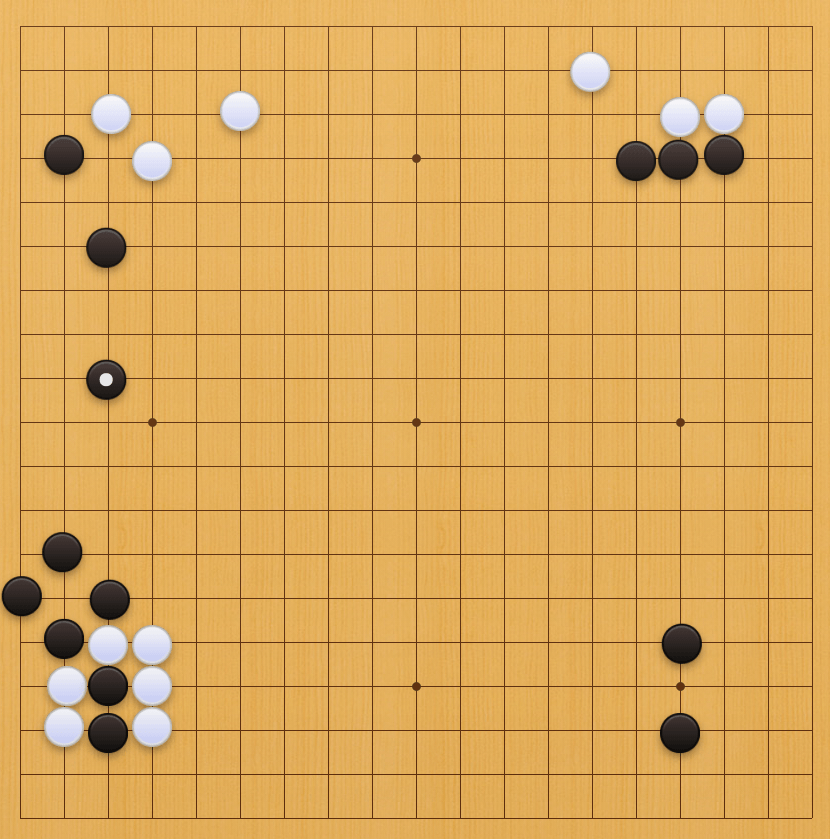

This question has two main parts: extracting sequences, and 80 gigabytes of games. The former is a challenge on its own, because it's nontrivial to find sequences in games. Consider the previous image and this one:

If you direct your attention to the top left again, you'll see the same shape as before. However, not only is there more on the board, making recognition of the sequence more challenging. The sequence is also at a different orientation. This means that we need to not only figure out how to work out symmetry and timing, but also filtering the global position to only consider regions of interest.

The second part of the challenge, the fact that the database is 80 gigabytes, is also difficult. It's large enough that we need to batch our processing, and ensure our analysis is somewhat efficient. So let's tackle the problems one at a time.

Filtering Patterns from Noise

When presented with the challenge and the two examples above, one's first instinct may be to set a distance threshold. Record moves that are within certain distances of each other, and analyze the resulting shapes. This is insufficient: moves can be somewhat far away and still part of joseki, and interference between patterns can be somewhat common. Attempting to work out this inconsistency threw me off for a few days, until eventually I found that someone else put more effort into the same problem.

The heroes of this story are Carson Leung et al. from the University of Manitoba, and their paper Data analytics on the board game Go for the discovery of interesting sequences of moves in joseki. He prescribes an algorithm (without providing any code) that goes like this:

- Maintain a list of four joseki sequences, one per corner.

- For each move, add it to one of the sequences if conditions are met.

- The distance is sufficiently small

- The sequence doesn't already have more than 20 moves (who wants to memorize that much?)

- The move isn't the same distance from multiple joseki

- Otherwise, add it to a fifth "Not Joseki" list, which is used in other computations.

The algorithm is a bit complex, but translating it to code turns out to be somewhat straightforward, and performant too. It processes about 400 games per second on my machine. Once the list of joseki is extracted, the next phase is merging them together, removing symmetry (de-reflecting) and tracking frequencies, into one large game tree. This relies on one of my favorite data structures, the Trie. Although in practice I just used a nested json object for easy serialization.

Once it's merged, we can just take the resulting Trie, prune it by some threshold (e.g. we might be only interested in joseki that appear in 1% of games or more), and save it to SGF (the serialization format for Go).

A note on the data

Now, unfortunately we can't just run this directly on the multi-gigabyte games file: we need some form of batching things. To do this, I decided to process the file one game at a time, only tracking those games which met our criteria. The filtering process when completed could handle about 20000 games per second, which is still a sizeable amount of time with over 25 million games, but it worked. Fortunately the data is still small enough that after preprocessing, I could put it into one batch.

There were a few filtering criteria I used. First, I restricted the set to only games with players of a certain strength: too weak and the moves quickly start to depart from balanced sequences. Additionally, I only considered non-handicap 19x19 games, as they're the games where standard joseki are applied the most. Finally, as mentioned, I only considered games during 2021.

Results

So, what is the most common joseki? Unfortunately, I already revealed it earlier, twice. The six-move sequence I showed is on the top of the list. I suppose it makes sense that I happened to choose that one, then. But you can see the rest of it in my upload to OGS here, sorted by frequency. Additionally, the full code is available on my Github.

As an aside, you should check out Go. It's a fun game.