Winning a Children's Game with Combinatorial Graph Theory

April 17, 2022

Playing a Children's Game

Recently a LinkedIn connection indirectly introduced me to this game called SET.

The rules are simple enough. 12 cards are dealt, all of which have images with four properties: color, number, shape, and texture. The challenge is to find sets of three cards such that, for each property, either all cards are the same or all cards are different.

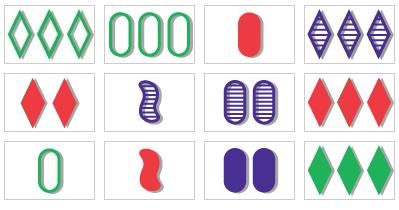

For example, in the above round, one such set is:

- Three hollow green diamonds.

- Three filled red diamonds.

- Three shaded purple diamonds.

In this case, the numbers and shapes match, but none of the textures nor colors match. It's worth noting here that it's possible with 12 cards to have no valid sets.

I spent about two minutes trying to find a few sets in my first game before declaring, "this is silly, I'm going to write a program to solve it for me." So that's exactly what I did.

Winning a Children's Game with Python

The first order of business is figuring out how to represent a dealing of cards in code. My first instinct was to convert all the cards to dictionaries storing the values:

{

"number": 3,

"texture": "hollow",

"color": "green",

"shape": "diamond"

}Unfortunately, this gets unwieldy quite fast, since typing out twelve cards like this takes quite a bit of work. Soon enough, I realized that we didn't need to store the full names of the card's attributes, but only a letter. And we didn't need to specifically declare what type of attribute it was, we could use an order to distinguish that. So we could encode 3 hollow green diamonds as 3hgd. Now we're in business, our earlier example game can be encoded as:

game = [

'3hgd', '3hgo', '1fro', '3spd',

'2frd', '1sps', '2spo', '3frd',

'1hgo', '1frs', '2fpo', '3fgd'

]Our cards now solidly written in code, the easiest way to continue is to try every possible triplet (using itertools) and see which ones work.

def compare(card1, card2):

# For each attribute, we only care if they're equal.

# Simply check for equality pairwise.

return [a == b for a, b in zip(card1, card2)]

def is_set(card1, card2, card3):

# The attributes must all be equal or all be unequal,

# test by checking every pair.

return compare(card1, card2) == compare(card2, card3) == compare(card1, card3)

def all_sets(game):

# Check every (unordered) combination of 3 cards.

for triplet in itertools.combinations(game, r=3):

if is_set(*triplet):

print(*triplet)Running this on our above game, we get:

3hgd 3spd 3frd

3hgd 2spo 1frs

3hgo 1fro 2spo

3hgo 2frd 1sps

3spd 1sps 2spo

1frs 2fpo 3fgd

Telling us that our game has six valid sets. A quick sanity check shows that our earlier example set for this game is in there, 3hgd 3spd 3frd. It turns out there's only

...But what if we could go faster?

Winning a Children's Game with Combinatorics

There's a peculiar property about the game that lets us shave off quite a bit of checking: given any two cards, the third card is fixed.

To see this, consider the cards 1fgd and 2hgd. For there to be a third card that forms a set with these, it must not share attributes with 1f and 2h since they're different, and it must share attributes with gd because they're the same. So the third card must be 3sgd.

Since the third card is fixed, that means that we can avoid checking every triplet. Instead, for every pair of cards, we only need to check if the third card has also been dealt. To start, we need to program a method to calculate the third card.

It turns out this is actually quite tricky with our current notation: we need to separately treat that the other values of 1 are 2 and 3 and the other values of h are f and s. To remedy this, we can simplify even more: it doesn't strictly matter what the exact values of the attributes are, so we can use the same convention for all of them. Let's use the digits 1, 2, 3 for all of them, and then every card is a 4-digit number. The set from right above can then be encoed as, for example, 1123 2223 3323.

With this, the third matching card can be calculated directly, which is quite easy using Python's generator syntax and built-in set difference:

def match(card1, card2):

return ''.join(

({'1', '2', '3'} - {a, b}).pop()

if a != b else a

for a, b in zip(card1, card2)

)

def all_sets(game):

for pair in itertools.combinations(game, r=2):

if match(*pair) in game:

print(*pair, match(*pair))As it stands, this will print out each triplet three times, one for each missing card. This can be fixed by checking if a found set has already been included, but it's not too important. It's actually a little more interesting to treat the game as "find at least one set" than "find all sets," so let's just do a light change:

def has_set(game):

for pair in itertools.combinations(game, r=2):

if match(*pair) in game:

return True

return FalseCompared to the decision version of the above brute-force algorithm, this solves 35000 puzzles per second, which is a solid performance improvement of about 440%.

But maybe we could go faster?

Winning a Children's Game with Interpolation

Okay, this one isn't that bad, but the name does sound really cool. In the above code, pay attention to this part: ({'1', '2', '3'} - {a, b}).pop(). The goal is to find which of the three attributes we're missing in our set of two, so we create a set of all three attributes, remove the two we have, and take (pop) what remains. This works fine, but for what it's doing, it's quite expensive.

We can directly look at the ASCII values of our characters here: 1 has an ASCII value of 49, 2 of 50, and 3 of 51. To calculate the third character given two characters, we can express this as a linear system of equations to see what function we need:

Plug it into your favorite symbolic calculator and we get

def match(card1, card2):

return ''.join(

chr(150 - ord(a) - ord(b))

if a != b else a

for a, b in zip(card1, card2)

)Comparing this to the previous one, now we solve 58000 puzzles per second, a nice 165% improvement.

Now I know what you're thinking: "Surely there must be a way to remove that if statement and compute the appropriate value in one go." There is! But it's both uglier and less efficient, so let's move on.

Winning a Children's Game with Combinatorial Graph Theory

We finally get to the original title of this post. I'll be assuming from here that you have an acute familiarity with Graph Theory.

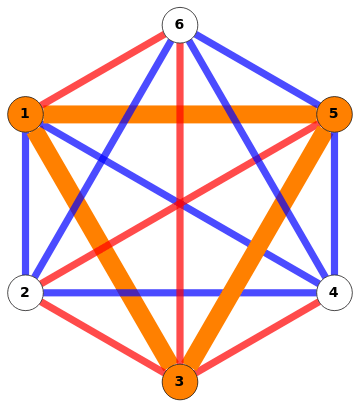

We can model SET as a complete graph with 12 vertices, one for each card. We can model the relations between cards using edge colorings. We'll assign one of 15 "colors" to each edge in the graph, and the color is defined by how similar the cards are. Using an operation resembling a bitwise XOR, the color can have a 1 in a position if the attributes have a different value and 0 if they're the same. So the color of the edge between 1123 and 1131 would be 0011. Given all relationships and the fact that no two cards are the same, we have each edge receiving one of 15 colors, which are really just bitstrings here.

Now our problem is just a matter of determining whether our complete graph contains a monochromatic clique of size 3. A clique is a subgraph where all vertices are directly connected (guaranteed with a complete graph), and a monochromatic clique is one where all of the edges are the same color.

Now, unfortunately I only knew enough graph theory to know that [Ramsey Theory] was involved somehow. After some time trying to see if I could do any better than the earlier

After following some citations for a while I land at this other paper which actually looks at this problem! It concludes that the algorithm is solvable in... drumroll...

So, that didn't really work. But oh well, part of the fun of math is that simple questions about children's games can lead to unsolved problems in graph theory.

But, one of the authors of that paper with the